A good fight

There was another shooting yesterday, this one motivated by the violence in Gaza. The shooter murdered two young Jewish people in Washington, D.C., and shouted “Free Palestine!” as the police took him away.

It’s hard to know what to say. Because I did not know the victims, the horror of their actual deaths registers as an abstraction. And I am ashamed of that. I can only imagine the gruesome scene of their deaths, and the grief that will follow their families throughout the rest of their lives.

Less than a week ago, someone bombed a fertility clinic in Palm Springs. One person died in that explosion. I didn’t know that person either. I didn’t know any of the victims of the October 7 Hamas-led attack on Israel. And I do not know any of the victims in Gaza.

Numerous other violent attacks have happened recently on U.S. soil, but the attacks in D.C. and Palm Springs stand out for their targeting of strangers for public violence in an attempt to gain widespread attention.

It feels like we have no language for such frequent losses. The more often such events take place, the harder it is to describe them in a way that seems appropriate. Their reporting can be easily overshadowed by the endless flow of new, new, ever-new information. It seems like we can’t talk about anything unless it’s happened in the last 24 hours. So these most recent acts of public violence will be diminished by tomorrow, except for those who personally knew the people killed. When violence becomes a trend, the particularity of its victims is lost. Instead of Sarah Milgrim and Yaron Lischinsky, we have simply another and another and another.

Violence against strangers has become alarmingly common. People we call “terrorists” write “manifestos” and engage in real-life violence to bring attention to their statements. After the shooting or the bombing, officials begin searching for a “motive” as if it is possible to explain murder, as if there is some sort of comprehension possible for such acts. Almost intuitively, we expect violence to be saying something, so we look for clues. Why do we assume violence is communicative? Why do we seek out manifestos and motives and narratives, as if these will help us understand? What exactly is it that we hope to get?

The shooter in D.C. left behind a manifesto that directly identifies his violence as a form of communication: “In the wake of an act people look for a text to fix its meaning, so here's an attempt.” At the end of the manifesto, he says he expects his actions to be “highly legible.” In other words, he thinks that people should “read” the shooting of Sarah and Yaron as a message.

It is a troubling idea that violence ought to be a form of communication. Why should it? In my book, I write about the notion of “excommunication.” I get this idea from scholars talking about the puzzle of how people could say something about not saying something. To “excommunicate” is to tell someone that you will never speak to them. It is communication about not communicating. In the book, I apply this idea to guns as a form of mediation, a kind of proxy mouth, and I consider how the presence of a gun itself can shut down communication. A gun can be a sign that someone will not engage in conversation with you, will not consider your opinions, will not stop to learn anything about the person the gun is aimed at. Guns are powerful symbols in a world where everyone wants to rage at everyone else online, but nobody wants to sit down and work out disagreements in person.

It’s hard to say if the gun causes the stoppage of engagement, or if the stoppage of engagement makes the gun seem reasonable. In the book, I call the gun a “one-keyed typewriter” saying simply “no” to personal encounter. We cannot talk to each other anymore.

I’m certainly not suggesting we should sit down with terrorists and have a chat. But I am suggesting that we have no room in our public life for hashing things out. We are habituated to the zinger, to the short tweet or skeet, to the trollish put-down. We don’t know how to argue productively. We don’t know how to disagree without trying to win something.

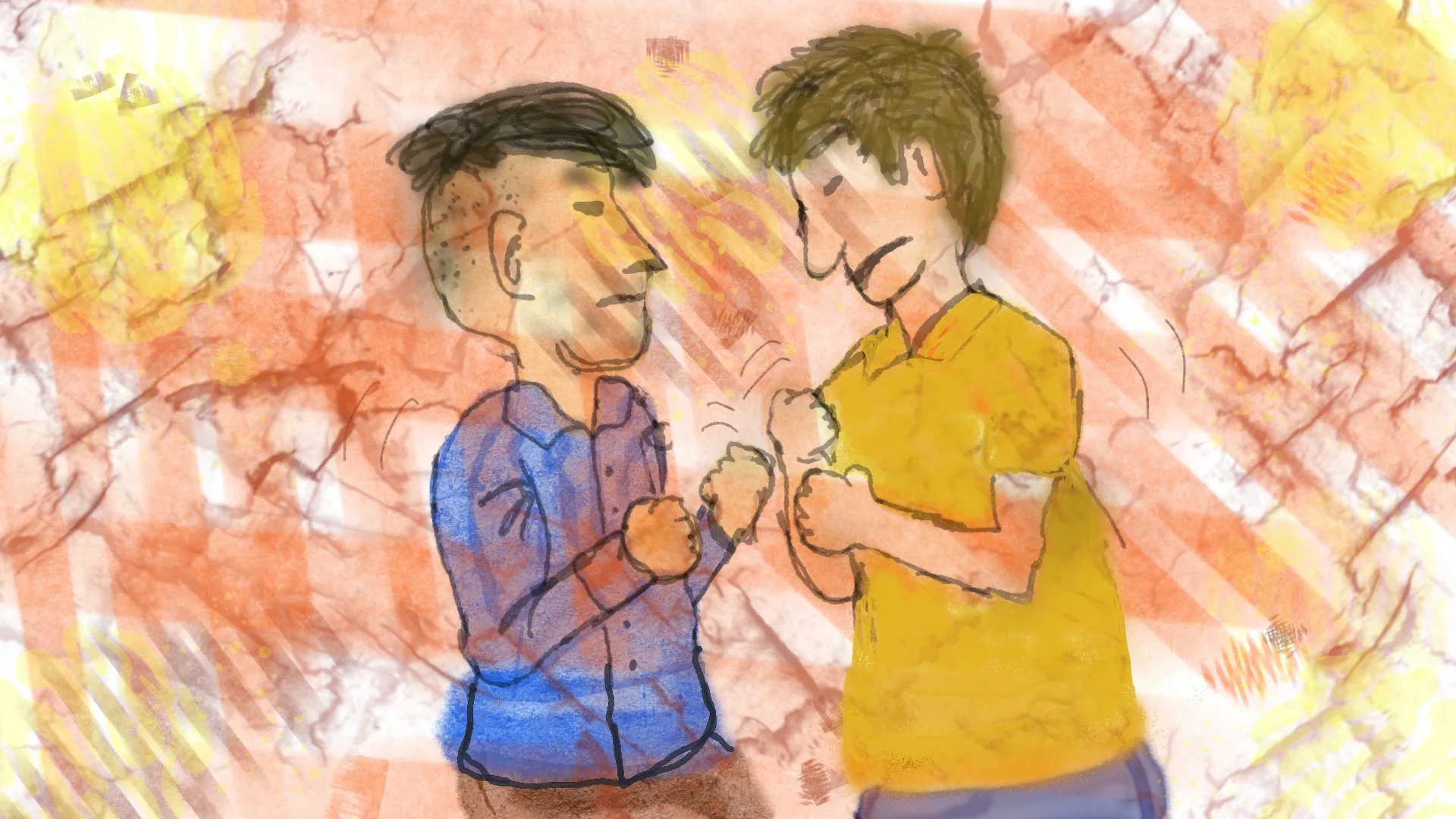

In his book Right Story, Wrong Story, Indigenous thinker Tyson Yunkaporta describes how a real-life conflict ought to unfold according to Aboriginal culture: “The fight would be intensely rule-governed and neither of us would be hurt too badly. it would not be about establishing a dominant ‘winner,’ but about both expressing our grievances explosively, getting it out of our system and then walking away with our dignity intact.” Such fights are personal. They take place between real people in a lived environment. He describes the values that shape such a conflict: “Dignity, mutual care and respect are our default settings.” Both people should be able to walk away afterward.

Online such conflicts cannot take place. Everyone is depersonalized. There is no clear beginning and end to a disagreement. Points are scored when other people jump in and “like” or “dislike” a comment, adding their own spin. People skip in and out of encounter. Some people aren’t even real.

It isn’t any surprise that we see online conflict as unsatisfying. But we have no protocol for disagreement these days, online or in real life. We have no habits for sitting down and working things out. We don’t even have habits for talking to each other.

Everyone I know is desperately lonely. Everyone I know is sick of online posturing, of the ever-increasing speed of encounter required online, of “posts” being the primary way we interact with each other.

I don’t know how to understand the exact contours of how our disconnectedness online leads to real-life acts of violence without good rules. I suspect it has something to do with our desperate need for real engagement with one another, and the fear that we won’t be heard without actual, embodied encounter. Actual, embodied encounter feels risky.

The decision to write a manifesto and then act in violent ways must have something to do with feeling unheard and unseen in other arenas. It is a profound failure of basic humanity to decide that this real-life encounter must involve bombs and guns.

We are a broken people, unable to meet one another eye-to-eye. We don’t know how to fight. So we huddle behind screens screeching at each other. Today, there will be a flurry of online outrage about the real-life murders in D.C., but tomorrow those victims will be forgotten by all but those who knew them.

We fight badly. We want to be ready, at any moment, to expel others from our lives. And simultaneously, we desperately want to let other people in.

I want to get to know you. I long to make you a cup of tea and sit on my front porch asking you questions and sharing my own views, without fearing you will kill me.

[For alerts about more writing, subscribe on the home page.]