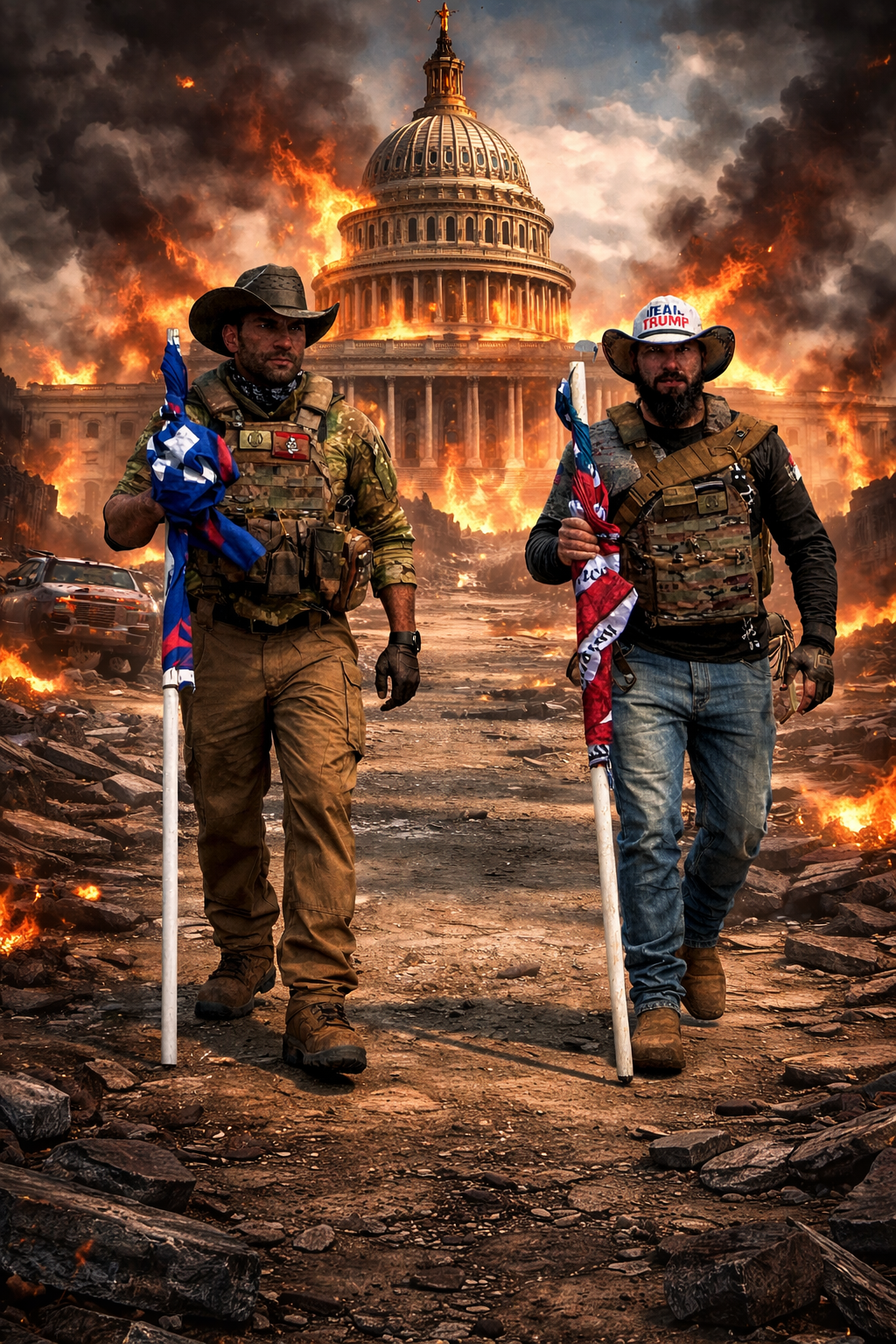

Riotous Play: January 6 as Pervasive LARP

[adapted from Cowboy Apocalyse: Religion and the Myth of the Vigilante Messiah; NYU 2025]

If we read the Capitol riot on January 6 as an alternative reality game (ARG) or pervasive larp (live-action role play), then we might ask what distinguishes reality from game in that context. And the answer is: Not much.

Theorists of pervasive games use the term bleed to refer to the degree of influence a game can have on the non-game lives of players. A Nordic collective of game designers describes bleed this way:

Bleed is experienced by the player when her thoughts and feelings are influenced by those of her character, or vice versa. With in creasing bleed, the border between player and character becomes more and more transparent. . . . A classic example of bleed is when a player’s affection for another player carries over into the game or influences her character’s perception of the other’s character. (Montola 2010)

The problem of bleed cropped up for larper Shoshanna Kessock when she played Dystopia Rising. In the game, three teams compete to escape from a post-apocalyptic war scenario. Amid props like barbed wire and tarps, there is an electric fireplace called the “Furnace.” Extras wander about moaning, dressed “something like concentration-camp inmates.” The allusions to the Holocaust are not accidental. Players must throw other players into the Furnace to escape and win the game. Kessock, who is Jewish, ultimately found the game intolerable. Half of her teammates, though, had no problem with the Furnace. To Kessock, the bleed was too great— and the game was too real (Simone 2014).

During a larp, play can become an alibi for troubling in-game actions. Perhaps it was this kind of mechanism that fueled the surprise of some when faced with legal repercussions for their actions on January 6. If the raid were just a playful form of trolling, then there ought to be no real- life consequences. This tension might also explain why Rep. Josh Hawley could raise his fist in solidarity with the protestors before they breached the Capitol but run and hide after. The bleed of the game was too real for him in the end.

In one post-apocalyptic larp, Ground Zero, players are locked into a basement bunker together. The game is set in the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis, in a world decimated by nuclear blast. There is no audience, and the gamemaster sits among the players. The place is filled with objects that function in both the larp and the real world at the same time: “Every object represents itself, [so] disbelief needs [sic] not be suspended. . . . The goal is to create a feeling of truly being there” (Stenros and Montola 2008, 7). Because people play as themselves, there is spillover of character traits between character and player (Harding 2007, 32). Holter uses religious language to describe how a player abandons his ego much as Christians say Christ performed kenosis (emptying of the divine self) in order to incarnate as a human being (2007, 20). Like those answering an altar call, players of pervasive larps choose to enter the imagined environment, choose to sink their identities into the characters they play, and choose to believe the world works as the game demands.

Another game with significant bleed is the intentionally repulsive Gang Rape. This freeform game is designed to maximize bleed effects without pressing players to the point of actual rape. Characters are paper-thin to force players to engage mostly as themselves. Players act out the events leading up to the rape (Montola 2010). Then they sit to narrate the parts they can’t act out. Players must look into one another’s eyes while describing sexual violence.

Gang Rape constitutes a near erasure of the magic circle by driving players into behavior considered disgusting, strange, or unnatural and forcing them to feel as if they are (nearly) performing those acts themselves (Montola 2010). The larp-generated world is not the same world in which players live, but the two worlds are in such close proximity the player is left uneasy. A similar set of uncomfortable feelings was evoked in the larp The Journey, based on Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. There, players enacted scenes involving murder, cannibalism, sexual manipulation, and abandonment. The designer “wanted people to feel a little bit dirty,” and to “have a bad feeling in their stomachs. . . . I wanted the potential for some really raw, really rough, really scary role-playing” (quoted in Montola 2010).

My interest here is the line—perhaps imperceptible—between extreme larping and the political action of today’s far right groups. Larps are typically framed as bounded experiences, with a beginning and an end, involving deep immersion but also at least intended to be distinct from everyday life. And yet some larps press at this distinction purposefully, like Gang Rape and Ground Zero. And some real- life actions, like the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville and the storming of the Capitol on January 6, seem fueled by a set of rules and narratives that are encountered in game-like ways. Indeed, participants seem to thrive in acting as if their most offensive activities are both very serious and not serious at all.

Jane McGonigal recognizes the tendency of pervasive games to make players more suspicious and more inquisitive. Players detect “game patterns in non- game places” and the “more a player chooses to believe, the more (and more interesting) opportunities are revealed” (McGonigal 2003). The physical world becomes an “endless source of information that is interpreted into the imaginary world” (Montola 2007, 180). The primary frame of real life is implicated in play.

Larping is an extraordinary example of how close to the primary frame a game can become. Because larp is a version of RPG [role-play game] that is acted out rather than described, players interact in a manner that could easily be miskeyed as the primary frame— instead of saying “I scream at him,” players actually do scream at other players. Larp participants have to be aware that the line between the performance frame and the primary frame is extremely thin and actions done in-character could be downkeyed and taken seriously instead. (Choy 2004, 60)

Success in a pervasive larp requires players develop what McGonigal calls “stereoscopic vision,” which “simultaneously perceive[s] the everyday reality and the game structure in order to generate a single, but layered and dynamic worldview” (McGonigal 2003). Players perceive a merged terrain of the game’s play and the real world. The effect can linger as players continue to see games where games don’t exist (McGonigal 2003). The player may achieve a “subjective, immersive state where they feel in a more or less pronounced way that they are the character in the game world” (Lukka 2014, 81). An immersed player may “lock their perspective to that of the character and attempt to uphold the diegetic reality” (85). To larp as a good guy is to have already committed oneself to that story regardless of actual events. The story is more important than the victims, who are objects in a preexisting plot.

The cowboy apocalypse can be viewed as an accelerationist pervasive larp. The game space—the magic circle of cowboy apocalypse imagination—is extended into real life as the good guy plays out a plotline to which he is already committed. The world is overwhelmed with evil and in need of a savior figure. To play the cowboy apocalypse as a larp is to view other people as props in the service of one’s own performance. It is to invest deeply in a vision of the future that celebrates one’s dominance, reinforced by the mythical celebration of white male hegemony in America’s past. The cowboy apocalypse can even be larped in retrospect—as it is imposed onto events that do not fit as they should.

People may act violently in order to authenticate their story. And just because the rioters were called off the Capitol grounds, there is reason to believe they still await the violence that will authenticate their cause. What happened on January 6 was not a game, despite its association with fandom practices. In tilting beyond the magic circle of play, participants borrowed the conventions of gaming to justify real violence. They imposed game rules onto the stuff of life, making their bodies and the very structures of Congress into the platform on which the game was played. Such activities remind us games are not by definition harmless. When the world is viewed as an apocalyptic game, it can become one.

SOURCES.

Choy, Edward. “Tilting at Windmills: The Theatricality of Role- Playing Games.” In Beyond Role and Play: Tools, Toys and Theory for Harnessing the Imagination, edited by Markus Montola and Jaakko Stenros, 53– 64. Helsinki: Ropecon, 2004.

Harding, Tobias. “Immersion Revisited: Role- Playing as Interpretation and Narrative.” In Lifelike, edited by Jesper Donnis, Morten Gade, and Line Thorup, 25– 33. Copenhagen: Projektgruppen KP07, 2007. In conjunction with the Knudepunkt 2007 conference.

Holter, Matthijs. “Stop Saying ‘Immersion!’” In Lifelike, edited by Jesper Donnis, Morten Gade, and Line Thorup, 19–24. Copenhagen: Projektgruppen KP07, 2007. In conjunction with the Knudepunkt 2007 conference.

Lukka, Lauri. “The Psychology of Immersion.” In The Cutting Edge of Nordic Larp, edited by Jon Back, 81– 92. Halmstad, Sweden: Knutpunkt, 2014.

McGonigal, Jane. “A Real Little Game: The Performance of Belief in Pervasive Play.” Conference Paper. Digital Games Research Association Conference Proceedings, Utrecht, Netherlands, November 2003. Accessed July 5, 2023. www.avantgame.com.

Montola, Markus. “Tangible Pleasures of Pervasive Role- Playing.” In Proceedings of DiGRA 2007 Situated Play Conference, edited by Akira Baba, 178–185. University of Tokyo, September 24–28, 2007.

Montola, Markus. “The Positive Negative Experience in Extreme Role- Playing.” In Proceedings of the 2010 International DiGRA Nordic Conference, Stockholm. “Experiencing Games: Games, Play, and Players,” August 16–17, 2010. www.digra.org.

Simone, Olivia. “LARP-ing at the Crematorium (in a Suburban Hyatt Hotel).” Tablet Magazine, September 2, 2014. Accessed July 5, 2023. www.tabletmag.com.

Stenros, Jaakko, and Markus Montola. “Introduction.” In Playground Worlds: Creating and Evaluating Experiences of Role-Playing Games, edited by Markus Montola and Jaako Stenros, 5–11. Helsinki: Ropecon, 2008.

Adapted from Tyler Merbler from USA, CC BY 2.0

<https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>via Wikimedia Commons